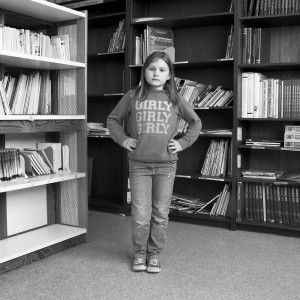

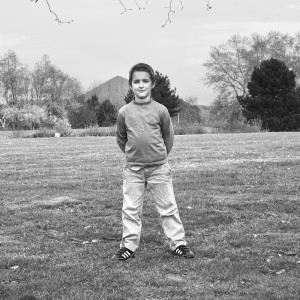

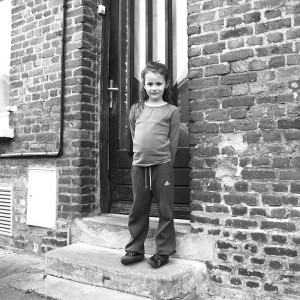

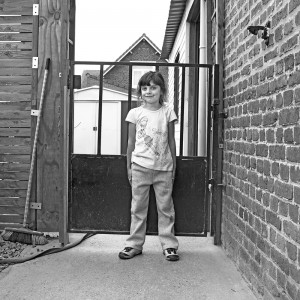

La série photographique est initiée dans le Bassin minier, à Liévin, auprès d’enfants de sept et huit ans d’une classe de primaire. Photographiés in situ dans un lieu qu’ils sont invités à choisir et qu’ils ne veulent pas voir disparaître, les portraits révèlent des enfants plus ou moins timides ou affirmés, des corps maladroits, fragiles ou solides. Ces vingt-cinq enfants deviennent des témoins vivants et des empreintes inconscientes des héritages historiques, sociaux, culturels et migratoires du territoire dans lequel ils ont grandi.

Territoire intimement lié à l’exploitation minière intensive qui a duré plus de deux siècles, le Bassin minier a ses caractéristiques propres, tant au niveau paysager (terrils), architectural (corons, cités jardins) qu’humain. La région a attiré des flux de travailleurs de différents pays, Belges et Algériens avant la première Guerre Mondiale, Polonais dans l’entre-deux guerres, Italiens à la Libération et Marocains jusqu’à la fin de l’exploitation minière. Depuis 2012, le Bassin minier est inscrit au Patrimoine mondial de l’humanité par l’Unesco au titre de « Paysage culturel évolutif et vivant ».

The photographic series was initiated in Liévin, in the mining basin of northern France, with seven- and eight-year-old children from a primary school class. Photographed in situ in a place they were invited to choose and which they did not want to see disappear, the portraits reveal children who are more or less shy or assertive, whose bodies are awkward, fragile or solid. These twenty-five children become living witnesses and unconscious imprints of the historical, social, cultural and migratory heritage of the territory in which they grew up.

A territory intimately linked to intensive mining which lasted for more than two centuries, the coalfield has its own characteristics, both in terms of landscape (slag heaps), architecture (corons, garden cities) and people. The region attracted workers from different countries, Belgians and Algerians before the First World War, Poles between the wars, Italians at the Liberation and Moroccans until the end of mining. Since 2012, the coalfield has been listed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO as a "living and evolving cultural landscape".